The coach of lost causes

Zdeněk Zeman’s quixotic ways.

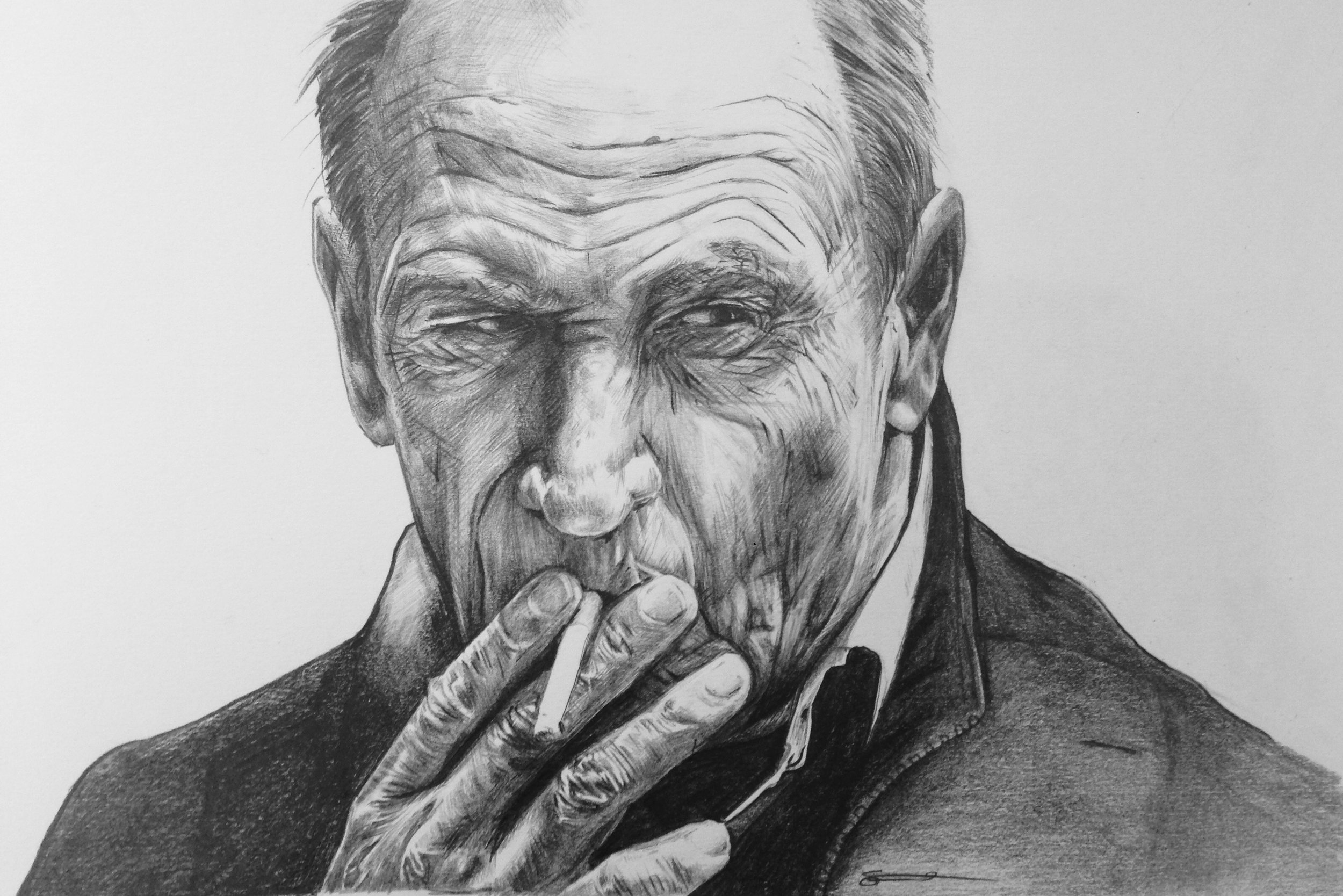

Drawing by Sammy Moody

Thore Haugstad

26 Mar 2016

Zdeněk Zeman, the chain-smoking cult manager, who has been part of Calcio for forty years, can in many ways be seen as the antithesis to the Italian football establishment. They call him Il Boemo, the Bohemian, for his refusal to conform. When he speaks, his voice is slow, deep and nearly monotone; his demeanour almost inexpressive. The same is not true of his football. Juxtaposed with a culture famed for catenaccio and winning at all costs, his wildly attacking tactics give him claim to be one of the least pragmatic elite coaches in modern times. If his teams are 1-0 up with minutes to go, they still attack as if the score is 0-0. His gruelling fitness methods have often drawn criticism, though as he once countered: “No one has ever died because of them.” When others have ridiculed his apathy towards any form of coherent defending, he has claimed not to understand their point. “Is a team that wins 1-0 more balanced than one with a 5-4 victory?” he asked Corriere dello Sport last year, according to Football Italia. “A 0-0 is boring, it’s better to lose 5-4. At least it gives you some excitement.”

The way Zeman sees football, modern influences have poisoned a sport that was once beautiful and pure. He has lamented the rise of money and politics, lambasted tactical killjoys, and launched explosive accusations against perceived cheaters and powerful institutions in situations where others would have kept schtum. The bravery of his stances have made him less famous for what he has won than for what he has come to represent. Dedicated to him are fan groups hailing his romantic ideals, a 2009 biopic titled Zemanlandia charting his rise, and a song called La coscienza di Zeman celebrating his sense of fair play—but since taking his first job in the 1970s, all he has won is one title in Serie C2 and two in Serie B. His principles have come at a price and, when he gave evidence in the Calciopoli hearing, La Repubblica summarised his career neatly by calling him “the beautiful coach of lost causes”. For his part, Zeman regrets nothing. “There is nothing dishonourable in coming last, if you do so with dignity,” he once said.

Zeman was born in Prague in 1947. His early years were spent playing ice hockey, volleyball, baseball and handball. He gave up football at sixteen. In the summer of 1968, he spent four months in Sicily with his maternal uncle Čestmír Vycpálek, a former winger for Juventus, Palermo and Parma, who would lead Juve to scudetti in 1971 and 1972. (He left the club in 1974, two years before the appointment of Giovanni Trapattoni.) While Zeman was in Sicily, Soviet soldiers invaded Czechoslovakia, so he stayed indefinitely. He got an Italian passport, married a Sicilian woman and studied sports medicine. At twenty-seven, he got a job at the Palermo academy, where he would spend the next nine years. According to Paddy Agnew in Forza Italia, his first role was with the U-12 team, where each training session earned him less than forty cents.

In 1983, Zeman became manager of Licata, a small club in Sicily. In his second season, they won one of the four groups in Serie C2 and got promoted to Serie C1. Already here, the statistics showed adventurous tendencies: Licata struck fifth-eight goals in thirty-four games and, while that may not sound that much, it was twenty more than any other side in the division. The promoted runners-up, Sorrento, hit twenty-eight; an average of 0.82 goals per game.

The triumph led Zeman to Foggia in Serie C1 in 1986, but he got sacked in his first season. A year later, he joined Parma in Serie B as the successor of Arrigo Sacchi. But many players had left with Sacchi, and a tough rebuilding job got him fired after seven games. The most memorable moment turned out to be an unlikely pre-season victory against the Real Madrid side of La Quinta del Buitre, who had just won the second of five consecutive league titles.

In 1988, Zeman returned to Sicily to coach Messina. They scored the most goals in Serie B, but also conceded the second most and duly finished in mid-table. One notable development was the rise of a striker named Salvatore Schillaci, who became the division’s top scorer with twenty-three goals. He soon earned a transfer to Juventus, shortly before Italy hosted the 1990 World Cup.

Schillaci was not the last talent to blossom under Zeman, nor the first. During Zeman’s nine years at Palermo, sixty youngsters turned professionals; in his final season, six local kids broke into the first team, in Serie B. “There are many coaches today who only manage, without trying to improve their players; it is the players who make the coach,” Zeman recently told Neue Zürcher Zeitung. “Then there are a few coaches who shape players. I feel like one of these few.”

The rules enforced by Zeman are not always reflected in his own behaviour. He supervises punishing fitness work, but smokes like a chimney; during a Blizzard interview, he was reported to average one cigarette every six minutes. (“I don’t count how many cigarettes I smoke every day,” he once said, according to the same interview. “Otherwise, I would become nervous and smoke even more.”) According to an article at SB Nation, contradictory behaviour also emerges in an anecdote from his time in Sicily, told by Guiseppe Sansonna, the director of his biopic, about his love for card games. Once, Zeman caught a group of players playing cards at way past bedtime. Rather than ordering everyone to sleep, he grabbed a chair and joined in. They played until dawn, after which Zeman fined the players—and himself.

In 1989, Zeman retuned to Foggia, who had been promoted to Serie B. The following years would be a fairytale that provided the plot for Zemanlandia. They won the league in his second season by outscoring their rivals by fourteen goals, and spent the next three years shocking Serie A with frenetic attacking football. (In that last Serie B season, even the defending was decent: they shipped thirty-six goals in thirty-eight games.) Drawing on his time at Palermo, Zeman launched the careers of youngsters such as Luigi Di Biagio, Francesco Baiano, José Antonio Chamot and Dan Petrescu. Once in the elite, Foggia came ninth and were only outscored by Fabio Capello’s AC Milan. They then came twelfth and ninth again, but could have entered the UEFA Cup had they beaten Marcello Lippi’s Napoli. After that season, Zeman left. A year later, Foggia were relegated.

When Zeman was once asked to explain his style, he referenced the Danubian school: a form of early tactical romanticism that, according to Jonathan Wilson’s Inverting the Pyramid, was developed by Eastern European intellectuals in the 1930s. Gathering in the coffee houses of Vienna, Budapest and Prague, they came to favour passing and team-work over the English values of dribbling and athleticism. The embodiment became the Austrian Wunderteam that reached the semi-finals at the 1934 World Cup and took silver at the 1936 Olympics. Inspired by Matthias Sindelar, the paper-thin forward dubbed ‘The Mozart of Football’ for his gifts, their football was artistic and imaginative. This remains the blueprint for Zeman. As he told the Blizzard: “I’ve only changed the rhythm.”

In more modern terms, Zeman’s values have been translated into an adventurous interpretation of the 4-3-3. The back line pushes up, the midfield marks zonally and the forwards press relentlessly. With the ball, there are few restrictions. The attacking trio are essentially strikers, the midfielders storm forward and the full-backs are defenders in name only. “Whenever we attack, all three forwards have to be in the penalty area, while two of the three midfielders come forward as well,” Zeman told the Wall Street Journal. “That way, the opponent is pinned back. Then you put the ball in the box, and because you have more men, you have more chances of scoring. It’s not rocket science. It’s simple math.”

The choice of 4-3-3 might hail from the teachings of Zeman’s idol. Romanian coach Ștefan Kovács succeeded Rinus Michels to lead Ajax to the European Cup in 1972 and 1973, just as Zeman was starting out. “He used to say that you have to defend by going forward,” Zeman told the Blizzard. “You don’t have to run after the opponents, because you have to face them front-on. In Italy, managers are afraid that losing a game might mean losing their job. That’s why most teams in Italy tend to not make the opponents play, rather than play themselves. You have to make every effort in order to win and not in order to avoid defeat or not to lose. That’s miles away from my mentality.”

At kick-offs, it is not unusual to see Zeman’s teams shaped in a 2-0-8 formation. Two players line up on forty yards, while eight stand on the halfway line, ready to sprint into the opposition half. Apart from that, the 4-3-3 structure never changes, nor does the mentality. “I don’t understand coaches who alternate between three or four systems,” he told Neue Zürcher Zeitung. “For me, after forty years in coaching, it is difficult enough just to implement this one.”

The passing style is closer to Marcelo Bielsa than to Barcelona and Johan Cruyff; Zeman demands fast and vertical moves that catch opponents off guard. “In my football, I try to eliminate pointless things, so for me a horizontal pass is futile, as it’s just loaning each other the ball,” he once said, according to Football Italia. “We must always try to do something that will have meaning.”

This ratchets up the intensity, which in turn requires stamina, so Zeman works his teams hard. His players run through forest, along beaches, up stadium steps. (One player said he “barely survived” his first training camp under Zeman; another called the methods “frightening”. It was not a compliment.) When critics say he merely exhausts his players, Zeman cites a different logic. “My training sessions may be long, repetitive and intense, but they’re fun,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “And when you’re having fun, you don’t get tired. Have you ever seen little kids running around all day long? Do they get tired?”

Modest facilities have rarely stopped him. At Foggia, according to These Football Times, the only thing Zeman had available was a pitch near a local youth club. When that was not free, he organised training in the parking area outside the stadium.

The extremity of his tactics puts him apart even among the most attacking coaches. Whereas strategists such as Bielsa, Pep Guardiola and Arsène Wenger see attractive football as the best way to get results, Zeman puts a higher value on entertainment. He adores La Liga for how some of the smaller teams stick to their style at intimidating grounds, and it is not difficult to imagine a congenial conversation between him and Paco Jémez.

Conversely, Zeman has attacked some of the pragmatists. He once claimed that coaches such as José Mourinho and Capello won only because they had the best players. “I could put my dead grandfather in charge of their teams, and they would still win,” he said. In 2009, he called Mourinho a “great communicator who hides well his own mediocrity”; Mourinho replied that he had barely heard of Zeman, and that he would look him up on Google to see what he had won.

But that dig will not have fazed Zeman. In his first season in Serie A with Foggia, his side beat Verona 5-0, drew 3-3 with Napoli and Fiorentina and 4-4 with Atalanta, and lost 5-2 to Lazio and 8-2 to Milan. As pure entertainment, it was unrivalled. “Many people appreciate me for it, and that makes me happy,” Zeman told Neue Zürcher Zeitung. “People go to the stadium because they want to see a spectacle, but there are games where you fall asleep. With my teams, that never happens.”

The success at Foggia gave Zeman his first top job. In 1994, he joined Lazio, whom he took to second and third. In the first campaign alone, they trashed Milan (4-0), Napoli (5-1), Padova (5-1), his old Foggia side (7-1) and Fiorentina (8-2). (The goals could come in burst. Against Napoli, all six came in the first half; against Foggia, all eight came in the second.) The squad featured Chamot, Signori, Guiseppe Favalli, Roberto Di Matteo, Paul Gascoigne, Aron Winter, Alen Bokšić, Pierluigi Casiraghi and a young Alessandro Nesta. But the third season was underwhelming, and Zeman was fired in January. According to James Horncastle, the dismissal was not revealed to him until a group of journalist told him at a conference in Coverciano.

An angry Zeman swore revenge by aiming to win the scudetto with another club, though even he could not believe it when Roma called him to declare their interest. Horncastle writes that the conversation went like this:

“Buongiorno, it’s Franco Sensi, the president of Roma.”

“Oh, yeah,” Zeman replied. “And I’m Napoleon Bonaparte.” He then hung up.

But he did eventually join Roma in 1997, and took over a squad that had Cafu, Marco Delvecchio, Abel Balbo and a twenty-one-year-old Francesco Totti. Zeman adored Totti and still does; according to Horncastle, he believes him to be the greatest Italian footballer in the last fifty years alongside Gianni Rivera and Roberto Baggio. Zeman has said that Totti was “like a son to me”. When once asked to name the three greatest players in Italy, he replied: “Totti, Totti and Totti.”

Zeman started off by guiding Roma to fourth. It was their best position in ten years.

In August 1998, Zeman gave an interview to weekly magazine L’Espresso shortly after a series of doping scandals had rocked cycling. Implying that neither Calcio was clean, he called on football to “get out of the pharmacy”. “Players are under ever greater pressure and it gets harder and harder for them to resist the temptation of the magic little pill...” he said, according to Agnew. “I’m sure that many players in Serie A, probably even in my own Roma side, have difficulty giving up on certain substances.” He specifically mentioned Juventus and voiced suspicions over Gianluca Vialli and Alessandro Del Piero. Why did nobody tackle it? “Because football is too big a business,” Zeman said. “And it suits everyone’s interests not to look too closely at the negative aspects.”

The story exploded. Del Piero’s agent spoke of the “unacceptable damage” inflicted on his client’s reputation; Vialli called him a “terrorist”. Libel cases were filed.

Before long, a respected investigating magistrate named Raffaele Guariniello had taken up the case. Launching an inquiry that would last two years, he obtained the medical records and summoned a series of coaches, directors, and above all former Juventus players. The evidence gathered was enough to send the club on trial on the accusations of “sporting fraud” and “illegal use of medicines”. The spotlight was directed at the period between 1994 and 1998, in which Juventus won three Serie A titles and reached three Champions League finals under Lippi. The process would last five years, and involve a slew of prolific players, coaches, agents and doctors. In Calcio: A History of Italian Football academic and historian John Foot calls it “the most sensational doping investigation and trial in Italian football history”.

The people on trial were president Antonio Giraudo, club doctor Riccardo Agricola and a Turin pharmacist named Giovanni Rossano. Rossano settled his case before the trial and got a five-month suspended sentence. The trial itself opened a can of worms. As witnesses were summoned, writes Foot, many former players gave vague and uncooperative answers that infuriated the judge, and it became apparent that Juventus and other clubs had used medicines without informing the authorities. According to Foot, some suspected that the anti-doping agency, which happened to be based in Turin, had manipulated tests and destroyed medical records. In November 2004, Giraudo was absolved, while Agricola was handed a twenty-two-month suspended sentence. An unimpressed Zeman claimed many of the players had lied, and called for Lippi to resign from the Italy post.

The verdict did not satisfy Juventus either. They appealed the decision over Agricola and, in December 2005, all parties were absolved. That led to an appeal by the state. In March 2007 came the final verdict: according to Foot, the original sentences were upheld, but the statute of limitations meant that everyone walked free. That may seem like a positive outcome for the club, but Foot writes that “while Juventus escaped without penal consequences from the doping trials, their image had been gravely damaged by the whole affair”.

Understandably, Zeman’s comments did not make him popular with Juventus nor certain members of the Italian football establishment. As Roma embarked on another season, a series of refereeing decisions led Sensi to believe that the ‘system’—the ubiquitous, all-powerful elite that pulls the strings of Calcio behind the scenes—was punishing Zeman and, by extension, Roma. They eventually came fifth, a decent position delivered with more thrilling football, and Zeman’s position had seemed safe. But according to Horncastle, Sensi’s stance suddenly shifted. In summer, Zeman was fired. Some suspected the results were only partly to blame. “Someone has placed a veto on Zeman,” wrote Alessandro Capponi in La Repubblica, according to Horncastle. “Someone has said to Sensi: ‘either you sack Zeman, or Roma will never win.’”

The episode threw Zeman into a downward spiral. Forgetful stints followed at Napoli and Fenerbahçe. Unable to find a job in Serie A, he moved down to Serie B to take Salernitana to seventh and Avellino to second from bottom. He returned to the elite only in 2004, when Lecce took a gamble on him. A young squad led by a fresh-faced Mirko Vučinić came eleventh by outscoring every team in the division bar Juventus. Lecce also shipped seventy-three, an average of nearly two goals per game. (By comparison, Atalanta, who came last, conceded forty-five.) In the game away to Juventus, Zeman was heckled mercilessly.

(The Juventus affair would even extend to a family member. In September 2014, Football Italia reported that his son Karel, also a manager, had blamed a ‘Juventus-supporting referee’ after his semi-pro side Selargius had lost 6-0 to Lupa Castelli Romani. Apparently, the referee had asked him in a mocking way whether he was Zdeněk’s son. “I knew we’d lose even before the game started," Karel said.)

Zeman resigned from Lecce at the end of the season. It had been another respectable campaign, but it took him nine months to get another job. When he did, it was with Brescia in Serie B.

Further failures loomed. He quickly resigned, and returned to Lecce in 2006, who had been relegated to Serie B. He got fired in December. He endured a disastrous spell at Red Star Belgrade, where he was dismissed after five games having lost a UEFA Cup qualifier to APOEL FC and led the club to the bottom of the table for the first time in twenty-four years.

By 2009, Zeman had endured a decade of disappointments. That year, when summoned as part of the Calciopoli investigation, he accused Luciano Moggi, the ex-Juventus chairman and protagonist in the scandal, of having run a campaign against him in which presidents had been discouraged from hiring him. At other clubs, he claimed, he had been forced out. “I won no titles because of the system,” he said, according to La Repubblica. Only last year, Zeman was asked about the title Capello won after replacing him at Roma. “Perhaps because if I had stayed, we would not have won for other reasons,” he told Corriere dello Sport, according to Football Italia. “If you think of Calciopoli, you will understand.”

By now, Zeman seemed all but finished. But there was one club willing to give him a chance. In 2010, he returned for a third spell at his beloved Foggia, in Serie C1, in a bid to revive the old magic. The results that followed were not bad: they came sixth in their section, having scored sixty-seven goals, of which Lorenzo Insigne, on loan from Napoli, struck nineteen. Yet Zeman walked away after the campaign. “The problem with Foggia was exactly this: you couldn’t buy any players, only have them on loan,” he told the Blizzard. “And then you would have to start everything again every season. In any case, many of those players have the opportunity to play at a higher level; to me that’s another achievement. Perhaps it’s because I’m getting older, but I feel good with youngsters. I hope I can keep teaching them things for some more time.”

The sojourn gave Zeman a second wind. The following year, he became coach and technical director at Pescara, in Serie B, where he was greeted by nearly three thousand supporters. His recipe had not changed. He signed Insigne again and recruit another young forward on loan, named Ciro Immobile. The 4-3-3 was wheeled out. The system had no natural role for talented attacking midfielder Marco Verratti, so Zeman converted him into a deep-lying playmaker, telling him that as long as he did fewer back heels, it would all be fine.

Everything clicked. Pescara became a sensational story, winning Serie B by scoring ninety goals in forty-two matches; twenty-seven more than any other team. Even Juventus scored fewer in their year in Serie B in 2006/07. The protagonists were Insigne, Immobile and Verratti, whose careers soon rocketed: Insigne made the Napoli first team, Verratti joined Paris Saint-Germain and Immobile would become top scorer in Serie A with Torino two years later.

Zeman had also been rejuvenated. Back at Roma, romantic general director Franco Baldini had failed to recreate a Barça-style project led by Luis Enrique, and fans soon campaigned for a sensational Zeman return. In summer, it happened: Roma hired Zeman.

“I hope to give Roma what I could not in my first two years here,” Zeman said, according to Football Italia. “Our work aims to bring enjoyment to me, the players and the fans.”

Would he perhaps defend a bit more this time?

“If you score ninety goals, it shouldn’t really worry you how many are conceded.”

Would he at least be more careful on the road?

“We play the same way, whether home or away. With Pescara this season, we scored forty-five goals at home and forty-five on our travels.”

But surely his fitness training had evolved by now?

“I’ve been told I’m old-fashioned. The more you work, the better you get, so I’ll bring back the double training sessions.”

Sadly for Zeman, the success at Pescara was not repeated. He fell out with key players, most notably Daniele De Rossi, and his tactics triggered familiar accusations. By November, Roma had dropped fourteen points from winning positions. “Zeman is truly a dreamer,” wrote Massimo Mauro in La Repubblica, according to the Guardian. “Always the same football, always the same defeats, and yet he never takes a step back.”

In February, Zeman was sacked after a 4-2 defeat at home to Cagliari. The team were joint top scorers alongside Juventus, but had shipped five goals more than everyone bar Pescara. The forwards would finish the season with respectable individual records in Serie A: Totti got twelve goals and twelve assists; Érik Lamela hit fifteen goals in thirty-three games, having scored four in twenty-nine the year before; Pablo Daniel Osvaldo struck sixteen. And yet when Zeman left, Roma were stuck in eighth. In 2015, Zeman would defend his methods and lament the club culture. “At Roma, the players do what they want,” he said, according to Football Italia. “I always had twelve on the treatment table and two stuck on the motorway, so I wasn’t happy with that. There is a sense of professionalism that needs to be nurtured, always, and that’s what I was aiming for. The trouble with Roma is that they want the maximum result with the minimum effort.”

The ending left Zeman bitter. He felt too many had lacked belief his methods, which led him to question why Roma had hired him at all. Totti later admitted that if every player had given everything, it could have gone differently. “My biggest mistake was thinking that everyone at Roma had my enthusiasm and heart,” Zeman said.

Afterwards, a group of Roma fans asked Zeman whether he would now retire.

“They’d have to shoot me first,” he replied.

In 2014, Zeman got another chance, this time at Cagliari. His motivation was not of the romantic kind. “I chose Cagliari because they called me,” he told Tuttosport, according to Football Italia. “If someone else had called, I’d probably be elsewhere.”

The target was an eighth-place finish, but results were poor and, in April, a group of fed-up ultras broke into the training ground as the squad were having dinner. La Gazzetta dello Sport wrote that several players were insulted and threatened. The club hierarchy dressed it up as a “tough and lively confrontation”, but Zeman verged from the party line and said the players were “shocked and upset”. They were certainly not inspired, for Zeman was sacked in December after one win in twelve games. By March, however, his successor Gianfranco Zola had also been booted out, and Zeman was reinstalled. He resigned five games later. Cagliari were relegated.

Last summer, Zeman went abroad again to join FC Lugano, a Swiss club based so close to the Italian border that the predominant language is Italian. He is now sixty-eight. The club had just been promoted to the elite, and the job resembled another step down in a career that seems to be fading out. But even now, Zeman maintains that his failures are attributable to external factors: politics, conspiracies, weak club presidents, unprofessional players. Most might scoff at his aversion to introspection, though in 2014 Sacchi leapt to his defence with a lyrical salute.

“Zeman only fails when he reaches clubs with players who are not prepared to work his way,” Sacchi wrote in La Gazzetta dello Sport, according to Football Italia. “His teams are a symphony of harmony and beauty. His players move with synchronicity, pace, fluidity and character. His squads have an undeniable identity; entertainment is assured, boredom and a waste of time banned... Zeman does not perform miracles, but he is one of the few geniuses in our football.”

Since going to Switzerland, Zeman has given numerous interviews reflecting on his career. In one, he rued the costs of his doping accusations. “I paid dearly, even with results on the pitch,” he told to Avvenire, according to Football Italia. “The system said ‘we won’t take you’, and my career took a different direction. I could have coached Milan, Inter or Real Madrid.

“Were they even against me abroad? Of course, because everything starts from an internal system. But for me, where I coach has never been important. At Licata, Foggia or Pescara, my ideas of football have the same value as at Madrid or Barcelona.”

Did he miss working in Serie A?

“I’m always happy to come home, but I don’t miss anything.”

Why was he still in football?

“For fun. I don’t go to the movies, since they banned smoking, but on the bench I can stand there with a cigarette for two hours, and I still enjoy when my team makes a great move or piece of play. That’s all I seek. Otherwise, with the climate and the people in it, I’d have stopped long ago.”

On another occasion, when the Blizzard asked Zeman to pick his favourite game, he did not select a win but a 3-3 draw with Roma against Lazio. What had stuck in his mind was not the events on the pitch, but the behaviour of the fans. “They were so passionate that you felt you really wanted to do everything to make them happy,” he said. And that demands more than just a win. “Football is spectacle and people need to enjoy their time in the stadium,” he has said, according to Football Italia. “So without goals, how are they going to have fun? I’ll never change that idea.”

If there is an explanation for how Zeman has kept going through the decades, particularly the barren years since leaving Roma in 1999, it centres on his ability to connect with supporters. So many failures have littered his career, so many insults have followed his doping comments, so many criticisms have enveloped his tactics, but he has kept returning, taking unappealing jobs abroad or dropping down to Serie C1 just years after fighting for the scudetto. Had he cared more for what ordinary coaches would identify as success—results, trophies—his tactics would surely have changed long ago.

But the attraction for Zeman is not measured in numbers. His self-image is less resemblant of a business leader chasing results than a stage director tasked with drawing crowds to the theatre. What drives him is the appreciation of the fans. And if he can give them, even just for ninety minutes, a blissful distraction from their daily chores—a beautiful goal, a thrilling move, a game that puts smiles on their faces—then that will mean more to him than any normal win. “Sometimes we lost, and yet the team left the pitch to applause,” he told Neue Zürcher Zeitung late last year. “For me, that was the greatest thing.”

***