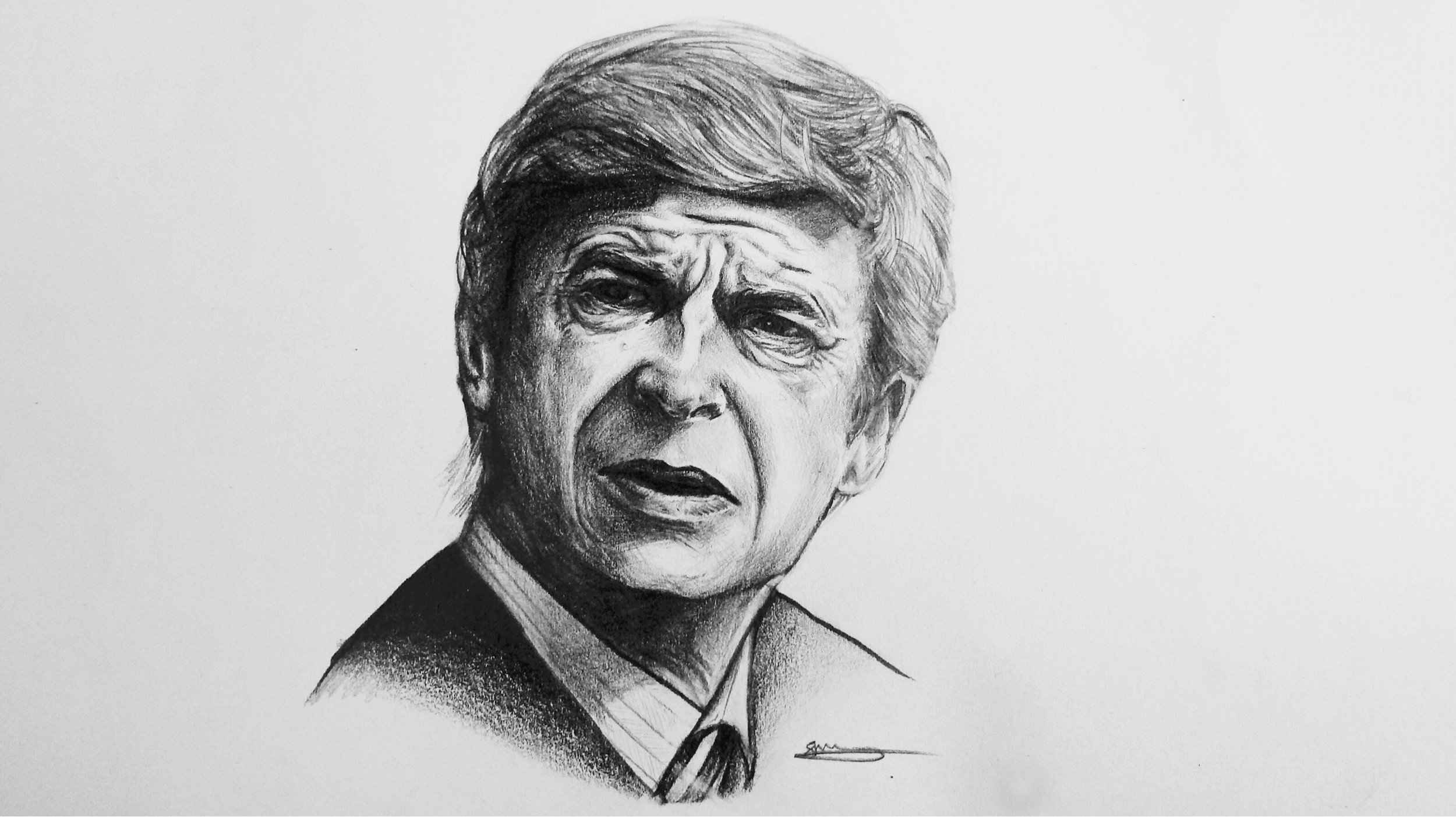

Le Professeur

The teachings of Arsène Wenger.

Drawing by Sammy Moody

Thore Haugstad

2 Apr 2015

In 2005, French biographer Xavier Rivoire was invited to the home of Arsène Wenger, in Totteridge, North London. The Invincibles were still admired and Wenger—studious, seclusive, outlandish—was perceived as the recherché architect of a football of breathtaking flow, speed and beauty. Few had seen this kind of play in England. Arsenal’s superficial elegance—the whirlwind breaks, the choreographed runs—had denoted a sophisticated system that only its creator understood. For Wenger, who would later say that the target of anything in life should be to do it so well that it becomes an art, it was the culmination of decades of painstaking study, and it might just have been worth it. The Invincibles were a masterpiece. Pundits and purists had extolled him like a concert audience leaping to its feet in applause.

The majority of Wenger’s spare time is spent at home. David Dein, the former Arsenal chairman, who instigated his appointment in 1996, jokes that the best car to buy second hand is Wenger’s, “because it doesn’t go anywhere. Literally, it goes to the training ground and back, and to the stadium every couple of weeks”. In seclusion, Wenger can be engrossed, gritty. One can imagine him perusing heavy passages until dawn flanked by towers of books on a desk scattered with empty espresso cups and scribbled notes. Other interests are compromised. Wenger loves art—a friend presides over a gallery in Nice—but he rarely goes out. He likes fine wines, but seldom drinks. After games, he shuns the tradition of sharing a glass of wine with rival managers; he prefers to go home. “He’s a very private man,” Dein told the BBC, “so apart from his family, his whole life is dedicated to football.”

Inside Wenger’s house, Rivoire discovered an unassuming decor. Wenger lives with his wife Annie Brosterhous, a former basketball player, who watches every Arsenal game at home. (“She is not a fanatic but she likes watching sports,” Wenger told the Independent, before conceding: “She does not have much choice.”) In his 2007 portrait of Wenger, Rivoire described the house as “a cocoon away from the outside world, where all is tranquil and undisturbed, an oasis of calm”. He took time to talk to an unnamed friend of Wenger who happened to be present. “There’s nothing flashy about the way they live at home,” the friend said. “Arsène leaves Annie to the finer details of household decoration, preferring to come home and put his feet up. He simply doesn’t have the time. After all, he has matches to watch, transfers to finalise, even books to read.”

Wenger’s eclecticism is renowned. He speaks French, German, English, Spanish, Italian, a bit of Japanese; he holds a degree in economics from Strasbourg University. At his home, Rivoire saw shelves loaded with heavy biographies, volumes on politics, history, religion. The books were in French and English. There were works on Julius Caesar, Pope Pius XII; The English, by Jeremy Paxman. Wenger watches political shows and societal debates, and holds clear views on geopolitical matters. In 2009, in a wide-ranging interview published by the Times and the Daily Mail, he forecast a world government that would address financial crookedness. “People continue to accept that fifty people in the world own forty per cent of the wealth,” he said. “Is that defendable humanly? Can you accept that when two billion people have two dollars to live per day? I don’t believe that will be accepted for much longer.”

Throughout Wenger’s career, this broad perspective has generated a collection of eloquent quotes. Once, when Sepp Blatter criticised top clubs for poaching youngsters, Wenger responded: “If you have a child who is a good musician, what is your first reaction? It is to put them into a good music school, not in an average one. So why should that not happen in football?” In 1998, when Arsenal had been booed by their own fans after drawing 1-1 with Middlesbrough, he said: “If you eat caviar every day, it’s difficult to return to sausages.” When Chelsea were reported to have tapped up Ashley Cole in a London hotel, Wenger remarked: “You cannot accept that people come under your window and talk to your wife every night without asking what’s happening here.” Another time, Wenger was asked whether he had received an apology Sir Alex Ferguson said he had sent to him. “No,” he replied. “Perhaps he sent it by horse.”

Within football, his studious nature makes him an anomaly. When Lee Dixon first saw Wenger, in 1996, he likened him to a geography teacher. Neither Dein needed much time to identify him as a highbrow. In 1989, with Ligue 1 on pause, Wenger showed up for a game at Highbury. At half-time, Dein introduced himself; the same night, the two had dinner with their wives at a friend’s house. The friend worked in show business and, late on, they played a game of reenacting characters. The conventional pick might have been a classic film, or a recent blockbuster. When the mantle passed to Wenger, he acted out A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the 16th-century comedy play by William Shakespeare. Dein: “I thought: ‘This guy’s something special. He’s a bit different.’”

Wenger was born in Strasbourg, the capital of Alsace, in eastern France, on the border to Germany. His family lived in Duttlenheim, a small village of about two thousand five hundred people, twenty kilometres southwest of the city. It was an agricultural community, devotedly Catholic. His father, Alphonse, ran an automobile spare-parts business in Strasbourg. He also owned a bistro with his wife, Louise, called La Croix d’Or. It was located close to their bourgeois home, where Wenger grew up with his older sister and brother.

The juvenile Wenger spent a lot of time in the bistro. It was an old-fashioned place. “I grew up in a pub where you did not see from here to the window because of the smoke,” he once said. Football stood strong in Duttlenheim, so players and managers often formed part of the clientele. “There is no better psychological education than growing up in a pub, because when you are five or six years old, you meet all different people and hear how cruel they can be to each other,” Wenger said in 2009. “From an early age you get a practical, psychological education to get into the minds of people... I learned about tactics and selection from the people talking about football in the pub—who plays on the left wing, and who should be in the team.”

Wenger played for the village side. Aged twelve, he was a slow midfielder with a buzzing mind. “He was always the technician, the strategist of the team,” Jean-Noël Huck, a team-mate, told the Guardian. “He was already getting his ideas across, but calmly... Arsène wasn’t the captain, and yet he was.” In the late 1960s, Wenger joined AS Mutzig, a neighbouring team reputed for playing the finest amateur football in Alsace. It was a step up, but it happened late. “I started to practice at the age of nine, but it was completely different to me—my first coach was when I was nineteen,” Wenger told FourFourTwo. “I thought it was just a dream because, living in such a small village, it seemed that footballers were on another planet entirely. My parents found it difficult to accept that their son, who worked so hard in school, could go to work in football. Back then, football was not a job for serious people. They wanted me to become a lawyer, or a doctor, or something like that. I needed to fight to convince my parents.”

The move catapulted Wenger into the third division. “He was always eager to learn,” Max Hild, the Mutzig coach, told Rivoire. “He wanted to know everything, from tactics to team strategy, to how to improve.” Wenger became more than a player to Hild. They loved to debate football and analyse games together. They would cross the border to watch the Bundesliga, at a time when German football was in vogue: West Germany had won the 1972 European Championship and the 1974 World Cup, while Bayern München had lifted the European Cup in 1974, 1975 and 1976. The excursions were not leisurely. Wenger and Hild would occasionally come home at four in the morning. “We’d stop on the motorway for a sandwich and a coffee, never a beer,” Hild told Rivoire. “I’ve rarely ever seen Arsène drink...”

The Germanisation of Alsace shaped Wenger in several ways. Hild: “The fact that we border Germany has rubbed off on us and given us a discipline and dedication which is, I suppose, inexorably Teutonic. You can see it in Arsène’s desire to work feverishly. He’s good at what he does, is talented, but also methodical.” Wenger: “I was French, but with an influence from Germany. Even in the way I see football, I feel it.” Germany also built his sense of internationalism. “I was born just after the war, I was brought up to hate Germany,” he said in 2009. “But that excited my curiosity because, when I went over the border, I saw that German people were no different, they just wanted to be happy too, and I thought it was completely stupid to hate them. So that is what made me want to live all over the world.”

Four years after joining Mutzig, Wenger moved to Mulhouse in the second division. The club had just turned professional and put him on £50 a week. It was an hour’s drive from Strasbourg, so he combined his career with a degree in economics at Strasbourg University. He represented the student football team. When they flew to Uruguay for the World Student Football Championship, in 1976, he joined the squad despite knowing that an injury meant he could not play. He carried equipment, made jokes and commented on tactics. Jean-Luc Arribart, the team captain, told Rivoire: “By the end of that trip, Arsène had almost taken on the role of assistant coach and team joker rolled into one.”

Wenger struggled to win a place at Mulhouse. Later, the coach was sacked and replaced with Paul Frantz. Frantz had coached RC Strasbourg in the 1960s and, like Wenger, he lived in the city. The two would discuss football on the commute. “Those journeys on the train actually served as a motivation for us,” Frantz told Rivoire. “I ended up using those chats we had to integrate Arsène into the team, where he effectively became my mouthpiece out on the pitch. He took the ideas we talked about in the carriage out onto the field, and he organised his team-mates along the lines we had talked about. I don’t think I ever had to tell him expressly to do that. He just took it on board naturally.”

Frantz saved Mulhouse from relegation and left. Wenger, tired of commuting, left too, and sought an employer closer to the city. Incidentally, an ambitious Strasbourg club named AS Vauban had hired Hild as coach. Wenger joined and the club did well. It led RC Strasbourg to recruit Hild as manager of their reserves. The senior side had just qualified for the UEFA Cup, so Hild was often dispatched to scout foreign opponents. That meant someone needed to fill in, and Hild recommended Wenger as caretaker. In 1978, at twenty-eight and with his career stalled, Wenger accepted the offer.

That summer, as his friends flew to Turkey and Greece, Wenger spent his holiday in Cambridge. He could not envisage a whole life in France and wanted to improve his English. He knocked on doors asking for a bed-and-breakfast stay. Coincidentally, the girl who came to offer it taught English in a nearby building. Wenger did a three-week course with kids aged twelve to fourteen. “I never worked so hard,” he said. “When I came back home, I started reading novels in English and underlined every word I didn’t know. And that’s how I learned it.” This was not his only educative expedition. He once stayed in Hungary for a month to observe the Communist system. He came home convinced it would never work.

Wenger’s role at Strasbourg evolved into that of a factotum. In the beginning, he was a player-manager for the reserves, and was occasionally called up as a sweeper for the senior side. When Strasbourg won the league title in 1979, for which Wenger had played a small part, he did not celebrate: he was busy working with the youth team. Later, when Hild became first-team manager, Wenger was handed further responsibilities. “I would drive six hundred miles to look for decent players,” Wenger told FourFourTwo. “Sometimes I would arrive two hours before the game started and stand behind the goal in the rain, and then drive home the same night. What people don’t know is that, when I was a young coach of thirty-one at the Strasbourg academy, I was coach, scout, physio, captain... everything. It was a fantastic education.”

In 1983, having retired as a player, Wenger accepted a role as assistant coach at AS Cannes, on the south coast. He rented from a painter an apartment that hardly had any furniture. He didn’t care. Plunging himself into work, he started reading specialist books and studying video. Richard Conte, the club’s general manager, told Rivoire: “I could turn up out of the blue at any time of night, and stay with him until whatever time in the morning, sitting in the chair next to him, but he’d stay fixed and obsessed with what was going on on the screen. He’d only really realise that I’d been there when I’d announce: ‘Right, good night then. See you later.’ That’s usually when he’d snap out of his trance and actually try to start a conversation.”

Wenger only stayed for a year. In 1984, Nancy needed a new manager, and Jean-Claude Cloët, a Cannes player who had been at Nancy, persuaded his former president to hire Wenger. “I assured him that Arsène could do the job with his eyes closed,” Cloët told Rivoire. “At Cannes, after only five weeks working under Wenger, I remember thinking to myself: ‘What the hell is he doing wasting his time here? He’s far too good for us.’”

It was not an easy start for Wenger. After a memorable 1970s, driven by a young Michel Platini, Nancy were now impecunious relegation strugglers. In Wenger’s first season, they finished in mid-table. In the second, they nearly went down. In the third, they did. Wenger did not take defeats lightly. Once, after a poor performance at Lens, he stopped the team coach to vomit in disgust. In his third season, when Nancy lost their last match before the winter break, he practically cancelled Christmas, locking himself away for a fortnight. Friends and family were barred from visiting. “When you are manager of Arsenal, if you lose a game, you drive home and you feel completely sick,” he would say in 2009. “Then you think as well of all the families at home whose weekend is dead because of it. So you feel that weight, that responsibility, too. Sometimes it is good to ignore it and become a bit selfish, though, because if you think about that too much you can become crazy.”

The relegation with Nancy had not deterred other suitors. AS Monaco hired Wenger in 1987. They bought Glenn Hoddle and Mark Hateley. (Another signing was Patrick Battiston, who had got his teeth kicked out by Harald Schumacher at the 1982 World Cup.) Wenger got Conte to find him an apartment a few hundred metres from the seafront. Before long, it was cluttered with videos. “We didn’t know Arsene before he signed us, but my first impressions were that he was very intense,” Hateley told the Daily Mail. “Every time you saw him he was in a tracksuit.” One player told Rivoire: “He virtually lived at the training ground, with his apartment back in Villefranche-sur-Mer anything but homely. All he had in his flat was a bed, a settee and his television. It was always in a right state, with clothes flung everywhere, and he’d never attempt to keep it tidy.” The three-room flat was supposed to be temporary until Wenger found something better. He ended up staying there for seven years.

On the training ground, Wenger put his analysis into practice. He primed his men for matches with forty-five-minute tactical lectures, and used statistical tools uncommon at the time. “He was tall and imposing, which helped, but he could command a room without raising his voice,” Claude Puel, who spent his whole career with Monaco, told the Guardian. “He always had that natural authority... He was the first manager I worked under who did specific tactical training, painstakingly going over video footage in preparation. He worked around the clock, constantly preparing the next session or reviewing the drills he’d put us through that day.”

Nothing was left to chance. Wenger appointed physiotherapists, sprint coaches, weight experts, dieticians. The drinking water was adjusted to room temperature to speed digestion. Red meats were replaced with chicken. Nobody was above the law. Once, when a chef tempted Wenger with a calorie-laden dish, he refused, insisting on eating the same food as the players. “We had masseurs,” Hoddle told the Daily Mail. “I had never had a massage at Tottenham. Players would have said you were soft. But over the months, we became more supple and, with a better diet, I was soon fitter than I had ever been.”

The changes paid off quickly. Monaco won Ligue 1 in Wenger’s first season. They would also lift the Coupe de France, in 1991, but few other trophies came their way. The obstacle was often Marseille. They had more fans, greater wealth, and lured several players directly from Monaco: Manuel Amoros, Rui Barros, Franck Sauzée. The president, Bernard Tapie, was a dominant and outspoken figure in French football, and often angered Wenger. Once, the two nearly came to blows. Marseille won four straight league titles, from 1989 to 1992, during which Monaco twice finished second and third. Wenger’s men also lost the cup final to Marseille in 1989 and, later, the final of the Cup Winners’ Cup, against Werder Bremen, in 1992. During these years, Wenger had not yet refined his emotional self-control. He smoked in the dugout to keep nerves in check. “The veins used to pop out of his head,” Hateley told the Daily Mail. “He was an absolute firebomb in the dressing room if he wasn’t getting what he wanted.”

In 1993, the Marseille player Jean-Jacques Eydelie was found to have asked three Valenciennes players to slack off in a league game between the two sides. The motive was for Marseille to wrap up the title early in order to focus on the Champions League final against AC Milan six days later. It was a scandal. Marseille were stripped of their league title, relegated to Ligue 2 for two years, and banned from next season’s Champions League. (Though having beaten Milan, they were allowed to keep the title.) Tapie was sent to prison. Wenger and others started to speculate about the size of the iceberg. “Look back now and you can’t help but think we might have claimed at least two more league titles at Marseille’s expense,” Puel told the Guardian. “He believes that too. It scarred Arsène. It scarred all of us.”

Earlier, Wenger had suspected bribes between Marseille and his own squad. In the spring of 1992, he and Jean Petit, his assistant, got one of the players to confess. Wenger thought he had evidence and Petit was prepared to testify in court, but they had no recording. “I wanted to warn people, make it public, but I couldn’t prove anything definitively,” Wenger said in 2006. “At that time, corruption and doping were big things, and there was nothing worse than knowing the cards were stacked against us from the beginning.”

Monaco would come second in 1993, behind Paris Saint-Germain. In 1994, they slumped to ninth. That summer, Bayern enquired about Wenger, but Monaco said no. After a poor start to the next season, they sacked him anyway. “He was rightly disappointed with the way it all ended, particularly given how much he would have liked to have gone to Bayern,” Puel told the Guardian. “That was an extraordinary opportunity for someone who spoke German and had grown up loving the Bundesliga. It would have been perfect.” The departure left a bittersweet taste. Towards the end, in an apparent reference to Marseille, Wenger said: “We are living in an environment where only winning counts. Anyone who loves sport knows that when two boxers enter the ring, there can only be one winner. Yet, for all that, for a good fight you need two heroes. Unfortunately, today, too much attention is paid to the winner. I find that sad. Cheats are forgiven, as long as they win.”

A few months later, Wenger flew to the United Arab Emirates to present an analysis on the 1994 World Cup to emerging coaches, at a technical conference hosted by FIFA. In attendance were a delegation from Japan, whose J. League had been founded the year before. In Japan, clubs are bankrolled by private companies, and Wenger was approached by representatives from Toyota, who owned Nagoya Grampus Eight. Grampus had just finished last in a league of twelve teams, but remained in the division because no relegation existed. Japanese football was a world alien to European thinkers. Wenger had doubts, but eventually accepted. “Arsène asked me to come with him,” Petit told Rivoire. “He said: ‘Listen, I’ll take you with me if you want. But I warn you—I’m going over there, and I have no idea whether I’ll like it or not. Who knows if I will be off again in six months?’”

Nagoya is one of Japan’s major ports, located by the Pacific Ocean, and one of the country’s largest industrial cities. Gary Lineker had just left town, having played for Grampus since 1992. The preceding season had lowered Toyota’s expectations: the target was to lose fewer games. Wenger spotted his first signing from his hotel room. One night, when watching a Brazilian league fixture, he saw a player he liked and tracked him down. It turned out to be Carlos Alexandre Torres, son of Carlos Alberto, the right-back who captained Brazil to victory at the 1970 World Cup.

Step by step, using an interpreter, Wenger installed his regime. Players were weighed prior to each training; those with excessive fat percentages risked exclusion from the squad. The mentality was different to that in France. “For a manager, it is a dream to have a Japanese player,” Wenger told a group of businessmen in 2013. “If you tell him to run ten laps, you haven’t even finished the sentence yet and he is already started. In Europe you have to convince the player that he has to run ten laps.” The Grampus players were accustomed to toil and sweat for four hours straight. Wenger limited the sessions to ninety minutes. “The players were discovering how to be professionals,” Wenger told Rivoire. “For the first time in my career, I had to hide the ball from players so they would stop training.”

The J. League followed an unorthodox format. Draws did not exist. Tied games went to golden goal, then penalties. Winners got three points; losers on penalties got one. The championship was divided into two parts; in each, fourteen teams met each other twice. The two league winners clashed in a two-legged play-off to decide the overall winner. Early on, it appeared unlikely to be Grampus. They lost seven of their first eight games. One day, when the chairman called him into his office, Wenger expected the sack.

‘I’ve taken a very big decision,’ the chairman said.

Wenger: ‘Yes, I understand...’

‘I will sack the translator.’

Wenger managed to save the interpreter, but uses the story to demonstrate the importance of communication. The Japanese language proved challenging even to him. “The kanji has two thousand different characters and the children at school have writing lessons every day until they are fourteen,” Wenger said. “And even then, they cannot read the newspaper—it takes so much time. In Japan, I only read the Japan Times—because it was in English.” The difficulties did bring some positives. Last year, Wenger used an anecdote to make a point about ignoring criticism from social media. “I took a great lesson in Japan, because in Japan at the start, I could not understand or read anything,” he told reporters. “So even a journalist who said I was absolutely useless, I welcomed him the next day in the press conference.”

It was not the only lesson of Asia. Wenger came to appreciate how linguistic mastery can aid cultural understanding. “The way sentences are built has a very big influence on the way people behave, and you penetrate much more the way people think, the way people behave,” he told the pupils. “I felt every time when I was in a foreign country, and I started to learn the language, I always had the feeling that I understood them more.”

He offered an example from Japanese. In English, you say: ‘I drink water’. In Japanese, you say: ‘I water drink’. The verb always comes last. “So people never switch off,” Wenger explained. “They always listen to you until the end of the sentence.

“If you say something to me, and I say: ‘I don’t agree with you, because...’, you already switch off, because you think, ‘I don’t agree with you’, and so you prepare something else to come back with.

“You have to listen until the end of the sentence to understand what people want.”

Grampus improved. Ten wins in the last eleven games elevated Wenger’s side to fourth. In the second part, they finished runners-up. Later that season, they won the national cup, named the Emperor’s Cup. The achievement was conspicuous and, in the summer of 1996, Wenger accepted an offer from Arsenal. His eighteen-month spell had been built on the principles of attacking football. “Our overall strategy didn’t change depending on the opponent,” one player said. “He always said that if we played to our own strengths, we could win.”

Later at Arsenal, Wenger would face calls to be more pragmatic. “Yes, but if I asked you who was the best team in the world, you would say Brazil,” he said in 2009. “And do they play good football? Yes. Which club won everything last year? Barcelona. Good football. I am not against being pragmatic, because it is pragmatic to make a good pass, not a bad one. If I have the ball, what do I do with it? Could anybody argue that a bad solution like just kicking it away is pragmatic just because, sometimes, it works by accident?”

He added: “I believe the target of anything in life should be to do it so well that it becomes an art. When you read some books they are fantastic, the writer touches something in you that you know you would not have brought out of yourself. He makes you discover something interesting in your life... What makes daily life interesting is that we try to transform it to something that is close to art. And football is like that. When I watch Barcelona, it is art.”

In 2009, Wenger said he originally intended to retire at fifty, but not now: “I never have days when I think I can live without football.” At sixty-five, he continues to lead a life of solitude, stoicism and sacrifice. “You want to have everything on your side that makes you competitive,” he said in the Times and Mail interview, that same year. “As a manager you have to live like a player.” It was put to him that that’s a long time to live like a player. “Yes, but for every passion there is a big price to pay,” Wenger countered. “I say that to the players. When you are hungry, it is only your stomach that is telling you it is hungry, it is just a part of your body. When you are hungry for success, it is the whole person, the whole life that wants that success. It is not just one part of your body that wants to win on Saturday afternoon, there is something in the structure of your personality that says this is vital to me and it is worth organising my life around this desire. That is the core of your life.

“I do a lot of things I do not like to do. I would prefer to be able to go out and enjoy my life. But I think that tomorrow I will be mentally dead, I will forget something, or I will not be competitive.”

Had he ever questioned whether football is important enough to dedicate your entire life to it?

“Of course.”

And...

“I decided that the most important thing in your life is to have a target and to go for it. All the rest is even more stressful. It is worse to have no target. You get up in the morning, you enjoy one minute, then the next minute, what do you do then?”

A year later, Wenger would analogise his perception of the nature of sacrifice. He told the Independent: “You know the story about the guy who’s a promising pianist? One day he goes to a concert and he hears a fantastic pianist. So he goes to see him after the concert, and says to him: ‘I would give my life to play like you.’ And the pianist replies: ‘That’s what I have done.’”

***